EMDR: Why I Sometimes Wave My Fingers In Front of Clients’ Faces

Key points:

This is a deep dive into the brain’s processing system works, and how EMDR can help when that system goes awry. If you’re more of a tl;dr kind of person, or if you’re just looking for a quick overview, you may prefer Shorts: An Introduction to EMDR Therapy

If your brain were one great big filing cabinet, it would be made up of a whole lot of individual files (brain cells), which would need to be grouped together and filed into drawers (memory networks) in order to be useful.

This is essentially how all mental patterns form. Brain cells (files) get grouped together into memory networks (drawers), which house all the relevant information associated with a particular idea or concept. From a brain perspective, mental patterns such as anxiety, depression, PTSD and addictions are no different.

In an ideal mental ecosystem, memory networks are highly interconnected, open and flexible. That is, the drawers are constantly being accessed and updated. Old files that are no longer relevant are thrown out, those that have been misfiled are recategorized, and new files are added.

Intensely emotional memories tend to be stored differently. Rather then being interconnected and open to updates, the more emotionally intense a memory is, the more siloed and inflexible it becomes.

EMDR helps create links between isolated memory networks and the rest of the brain, allowing them to be seen in context of the rest of the files and updated accordingly.

EMDR is one of only two types of psychotherapies The World Health Organization recommends for treatment for PTSD, and has proven effective in a number of other disorders, including depression, anxiety, phobias, addictions, chronic pain, boarderline personality disorder, and phantom limb pain

I like science. In the general sense, but more specifically, as it relates to psychotherapy. I like science-based, evidence-backed therapies. Which means I use EMDR. A lot.

It also means I need to explain EMDR. A lot.

And so, after giving my EMDR 101 speech to clients on a near daily basis, and equally as often making a mental note to write it down so I had a resource that I could refer clients to, I have finally gotten around to it.

So, here goes.

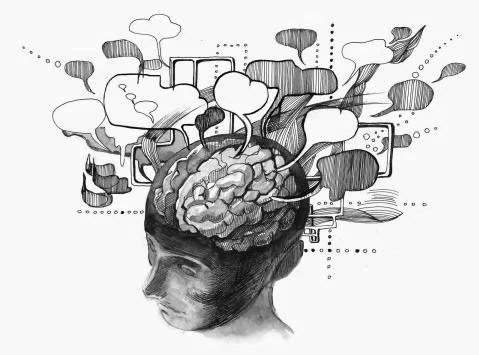

Understanding How Memories Are Processed in the Brain

EMDR, which stands for Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, is an evidence-based (ie. it’s been scientifically studied and proven effective), nervous system-centred (ie. it’s based in neurology and how our brain stores information) psychotherapy that targets neural circuitry responsible for the symptoms of mental distress. And if your eyes are beginning to glaze over, hold on! Metaphors and analogies are coming.

A bit of background.

How Memory Networks Form

Imagine our brain as a room with one giant filing cabinet in the centre of it. The filing cabinet is made up of many drawers ( memory networks), which are filled with many files (brain cells).

Our brains are made up of a whole bunch of files (100 billion to be, well, likely somewhat less than exact). At birth, most of these files are empty and strewn about the room haphazardly, with relatively few being stored in the filing cabinet.

During the course of our life, the files in the room are gradually organized into drawers of the filing cabinet. Files on cat, dog, horse and monkey go in the drawer labeled ‘animals.’ Files on mom, dad, brother and grandmother may go in the drawer labeled ‘family.’ If we’re lucky, duplicates may also go in the ‘happy childhood’ drawer.

This is essentially how learning happens. Brain cells (files) get grouped together into memory networks (drawers), which house all the relevant information associated with a particular idea or concept.

When we’re born, only about 25% of those 100 billion brain cells are connected together in memory networks. The other 75% of our brain wires together as we age, in response to what we learn from our environment.

All mental patterns form through brain cells wiring together into memory networks. This includes patterns associated with mental distress. There are specific memory networks associated with anxiety, depression and addictions, in the same way there are specific memory networks associated with animals, family and happy childhood.

In an ideal mental ecosystem, memory networks are highly interconnected, open and flexible; that is, the drawers are constantly being accessed and updated. Old files that are no longer relevant are thrown out (don’t need to know the precise decibel of cry that gets mom to pick me up now that I can yell her name), those that have been misfiled are recategorized (whoopse, turns out dad’s golf clubs do not belong in the ‘fun throw toys’ drawer), and new files are added (ah, so that’s what love feels like).

This flexibility means they can adapt to the current situation by allowing new information in and new learning to happen.

However, not all memory networks are quite as receptive to new information. This is especially true of intensely emotional memories.

How Trauma Impacts Memory and Processing

The Role of Emotion in Memory Storage

Information that is accompanied by intense emotional states (whether intensely negative emotion, as in anxiety, depression and PTSD, or intensely positive emotion, as in addictive behaviours) seems to be stored differently in our brains.

It’s as if these groups of files, rather than being organized in one of the cabinet drawers, are instead laminated and then used to wallpaper the filing room. Those files are accessible (often far too accessible, being triggered much more frequently than we’d like), but inflexible, disconnected from the rest of the filing cabinet, and out of context. Because they’re isolated and out of context, such files often have the feel of gross over generalizations.

Perhaps that time I used dad’s golf clubs as a throw toy, instead of generating a file that says ‘throwing gold clubs is bad’ and filing it away under ‘things not to do’ or ‘things that will be funny in 5 years but are decidedly not funny right now,’ I generate a shame-filled file that says ‘I am bad’ and paste it all over the walls so I don’t forget.

Why Traumatic Memories Become “Stuck”

The more emotionally intense a memory is, the more isolated, and therefore inflexible, it becomes. You can see it, but you can’t make changes to it.

Which makes some evolutionary sense. At some point in history, you can imagine it would have been a useful strategy that if something evoked an intense surge of fear, our brain etched it in stone to ensure we’d never make that mistake again.

In present day however, it often leaves us stuck, replaying versions of the past that are no longer useful.

So… how does this relate to EMDR?

Fair, enough background, let’s get on with it.

How EMDR Works to Reprocess Memories

So, we’ve got intensely emotional laminated files emblazoned on the walls of our brain, which don’t get updated as the times change and create the atmosphere under which all the other files are viewed.

Creating New Links Between Memory Networks

The magic of EMDR is in it’s ability to peel these isolated files off the wall and file them into the appropriate cabinet drawer, allowing them to be seen in context of the rest of the files and updated accordingly. More technically, EMDR connects isolated memory networks with the rest of the brain, such that those once siloed areas are able to receive new information and correct out-dated data.

As those memory networks become more connected, that ‘I am bad’ file can be accessed in conjunction with other files that hold information like ‘I was young,’ ‘I didn’t know any better,’ and ‘kids do the darnedest things.’ In the face of all that information, that ‘I am bad’ file can be updated and revised to ‘throwing golf clubs is a bad idea, but I’m not bad.’

During EMDR, both the isolated file and the appropriately categorized files that correspond to it are accessed. Then, all we need to do is help link those two areas of the brain, so that the once-isolated memory-network can be filed away.

The Role of Eye Movements in EMDR

Which is where the eye movement part of EMDR comes in. While the exact mechanism by which the eye movements work is uncertain, they help create connections between once isolated memory networks and their adaptive counterparts remains (if this uncertainty deters you, you may find it interesting that we don’t know the exact mechanism of action of many of our most popular pharmaceuticals, including many antidepressants and psychotropics).

Put another way, if an isolated memory network plays like a broken record, with old memories and behaviours getting repeated over and over, EMDR nudges the needle on that record player. It connects that isolated memory network to other memory networks, such that new information can process in and that old repeated pattern can be integrated into the context of the whole record (er, brain).

And for the sceptical of the bunch, here are a few facts, studies and resources to peruse:

In a meta-analysis of PTSD, EMDR was reported to be as or more effective than other mainstream therapies, including CBT, exposure therapy and pharmaceutical medication (SSRIs)

EMDR is one of only two types of psychotherapies The World Health Organization recommends for treatment for PTSD

EMDR has proven effective in a number of other disorders, including depression, anxiety, phobias, addictions, chronic pain, boarderline personality disorder, and phantom limb pain

To learn more, check out EMDR Canada

Looking for More?

If you’re interested in learning more about EMDR, we have lots of information to geek out on! You might enjoy: