WHEN THE PAST LIVES IN THE PRESENT

Any threat that overwhelms our ability to keep ourselves safe is inherently traumatizing to our nervous system.

Whether such a threat is real or perceived, whether it is physical, mental or emotional, makes no difference. Our nervous system does not discriminate between physical annihilation and annihilation of the self. Such situations directly conflict with our primary biological imperative: to survive. And when such a visceral drive is undermined, it has profound and lasting impact on our mind and body.

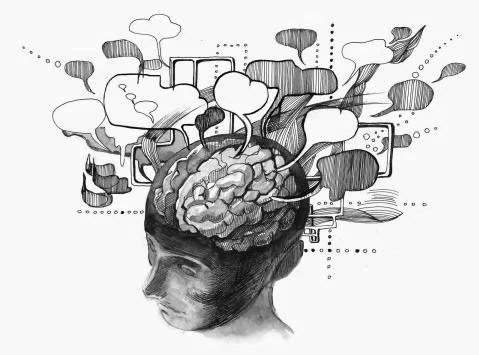

Trauma fundamentally changes the brain.

The amygdala, the part of our brain that governs fear and pleasure, becomes sensitized to threat and heightens fear and stress responses. Because of this, we become more reactive.

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that regulates emotional responses from the amygdala, becomes smaller and less functional. Because of this, we’re less able to control our emotions.

The hippocampus, the part of our brain that helps with recording, archiving and retrieving memories, becomes less active. Because of this, we’re less able to discriminate between past and present.

This is the legacy of trauma.

Trauma does not live in the mind, as a story of a difficult event that happened to us in the past. Trauma lives in the nervous system, as patterned responses that continue to happen to us day after day.

We live the stories of terror and disgust and shame, of hyper-reactivity and emotional dysregulation and desperate attempts to numb the pain, not as memories of past, but as day to day, moment to moment experiences and ways of being in the world.

But none of these changes are permanent. Trauma doesn’t have to be a life sentence.